AFTON — Star Valley ranchers will soon be voluntarily experimenting with rotational livestock techniques in hopes of reducing bacteria pollution from feces that has plagued the Salt River.

Keeping cattle and sheep on the move and away from the Salt are among many strategies being considered in a water quality restoration plan that’s nearing completion for the 890-square-mile watershed.

The plan is required by the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality and employs “Total Maximum Daily Load” mitigation targets that will ideally reduce E. coli bacteria levels in the Salt by 60 percent.

Tetra Tech project manager Ron Steg, who was contracted by the DEQ to craft the Salt plan, spoke June 10 at an Afton public meeting about the impetus for the restoration plan.

“In summary, Stump Creek and the Salt River exceed Wyoming’s water quality standards for bacteria,” Steg said. “DEQ — the state — is required by the Clean Water Act to prepare a plan in cases where water quality standards are exceeded to achieve water quality standards.”

The plan is not regulatory, it’s purely voluntary, Steg said.

DEQ’s plan for the Salt, years in the making, has been completed and is now out for public comment.

While bacteria pollution within the Salt watershed is traced to a handful of sources, the most significant contributor by far is livestock production. Charts that Steg presented at the meeting showed there are as many as 32,000 sheep and 10,000 cattle grazing within the Salt watershed, and together they account for between 88 and 95 percent of the E. coli going into the watershed.

“One of the most significant sources in the watershed is livestock,” Steg said. “Where are you going to go to address this problem in this watershed? I’m looking at this pie chart, and you need to address livestock and you need to address human sources.”

Studies have found that in a day a single cow produces about 33 billion fecal coliform bacteria — three times more bacteria than a sheep. It takes 41 geese, 16.5 humans or 165,000 beavers to produce the same bacteria load as a head of cattle, according to data Steg presented.

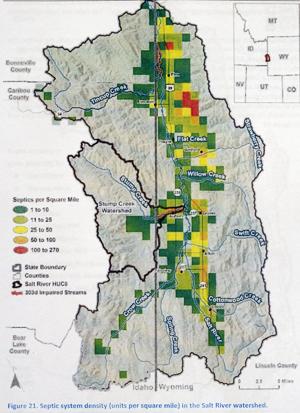

Human contributions to the Salt’s bacteria load are believed to be from faulty septic systems, a wastewater treatment plant, RV waste tanks and human recreation.

The underlying concern about high bacteria counts in Star Valley’s largest drainage is health and human safety.

“The real issue is people can get sick,” Steg said. “Typically symptoms of E. coli infection include things very similar to flu-like symptoms: abdominal cramps, diarrhea, low-grade fever.

“This is not the kind of thing where the cause and effect is obvious,” he said. “It’s not like you jump in the creek and by the time you get to the truck on the way home you’re sick and throwing up.”

Symptoms, Steg said, don’t set in for a couple of days and potentially as long as a week.

While there have been no recent outbreaks of illness traced to the Salt’s E. coli problem, there have been problems within the watershed in the past.

“This is something that’s real and actually can happen,” Steg said. “Although this was a groundwater issue, back in 1998 there was an outbreak of E. coli infections that occurred in Alpine with 150-some people getting sick.”

The DEQ and Star Valley Conservation District have not been monitoring groundwater, but rather surface water since 2005 taken at nine samples sites in the mainstem Salt and one in its tributary, Stump Creek.

While there have been blips here or there, the E. coli trend has on the whole been stagnant.

“There don’t appear to be any long-term up or down trends,” Steg said. “It seems to be relatively constant. I think the bacteria levels tend to be a little higher in June and July, but from year to year … there aren’t any trends that you see.”

Only a handful of Star Valley residents showed up to the meeting to hear Steg present some of the proposed solutions. All E. coli sources are being targeted for mitigation, he said.

For problems relating to humans, education is at the forefront of the plan. A cost-share program for Star Valley septic systems is being pursued, and there are also hopes of using grant money to split the cost of systems that need to be replaced.

“For all of this it’s contingent upon receiving grant funding,” Steg said.

To help reduce dog waste, solutions could be as simple as installing mutt-mitt stations near boat landings.

“What this plan includes is a whole lot of practical, sort of simple solutions for a simple problem,” Steg said. “There’s not a lot of technical detail in this plan.”

For E. coli pollution from livestock, proposed solutions include educating ranchers about best practices for stockmanship through workshops.

Jim Norman, who manages Cakebread Ranch, spoke at the meeting about strategies he’s already experimented with to keep cattle away from the Salt. Erecting creative temporary fences is one tactic being used to limit livestock access, he said.

“With good stockmanship and low-stress handling you can park a herd of cattle without fences, and it will remain there until you move this,” Norman said at the meeting. “The last ranch I was on was 15,000 acres, and we only had a perimeter fence.

“This is one opportunity that I would think would allow some significant impact without changing necessarily the livelihood of people who raise stock in the valley,” he said.

Public lands grazing allotment demonstration projects are also underway within the Salt watershed, and equivalent projects on private lands are also being pursued.

Star Valley’s stockmen are still warming up to the idea of some of the voluntary measures being proposed by the plan, Norman said in an interview.

“It’s hard to change cattleman,” Norman said. “Some are interested [in the strategies], some have no interest whatsoever.

“As a general rule I think every rancher looking at this sees regulation coming,” he said.

Contact Mike Koshmrl at 732-7067 or [email protected].