The native Colorado River strain of cutthroat trout, a species that is struggling across much of its range, is barely holding on to existence in the headwaters of the Green River.

Non-native brook trout introduced by managers decades ago have slowly and steadily invaded the drainage, pushing the slower-growing native trout out of the vast majority of its range. And the displacement is not historic but, rather, fluid and ongoing.

“In the Upper Green project area, in most places, brook trout now have some influence or have completely taken over the watershed,” fisheries biologist Matt Anderson said.

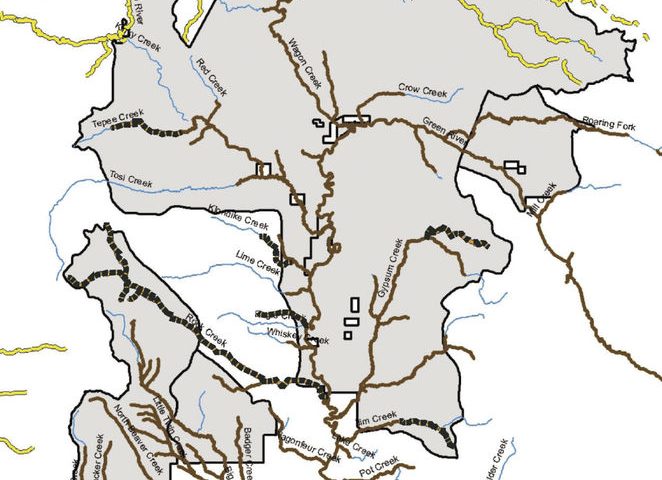

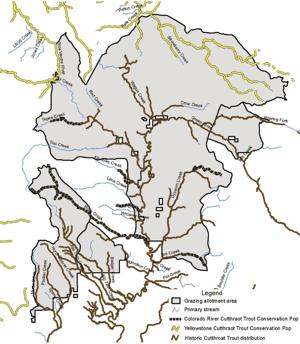

When Anderson and others recently surveyed 217 miles of Green River tributaries they found cutthroat still hanging on in just 27 miles. Most of that remaining habitat, however, had been “extensively invaded” and is now dominated by brookies. The Colorado strain of cutthroat now exists alone and unimpaired in a single stream: diminutive Klondike Creek.

“The vast majority of their historic range has been lost,” Anderson said. “They’re no longer present, and they were once present through the main rivers — the Green, New Fork — and all the tributaries.”

Anderson, a former Bridger-Teton National Forest employee who has since moved on to the Ozark National Forest, assessed the state of fisheries on 264 square miles of the Bridger-Teton for a report that supplements the ongoing environmental analysis of a large Upper Green River area grazing allotment.

Cattle grazing, he found, was not a significant factor affecting the suitability of streams for cutthroat: More than 84 percent of streams surveyed were in “class one” condition, with scant erosion and healthy riparian vegetation.

A grazing management proposal favored by the Bridger-Teton would “impact individuals and habitat,” but would not drive down Colorado River cutthroat populations or increase the species’ need to be protected by the Endangered Species Act, Anderson concluded.

But Anderson found several waterways where brook trout, a species native to the Great Lakes and Eastern seaboard, are overtaking the system. That’s the case at Rock Creek, which drains off the north side of Tosi Peak into remote country before running into the Green River near Kendall Valley Lodge. Despite being managed as a Colorado River cutthroat trout conservation population, Rock Creek now supports “very low” numbers of the native species.

“This population is being invaded by brook trout,” Anderson wrote, “which has led to reduced cutthroat densities despite efforts to actively remove brook trout from the stream from 2011 through 2013.”

The same elsewhere

It was a similar story in Tepee Creek, a tributary of Tosi, which supports another conservation population of cutthroat that are being overwhelmed by brook trout. Tepee’s cutthroat, Anderson found, are in “danger of extirpation from non-native invasion” and are persisting in degraded habitat.

In Gypsum Creek, on the east side of the Green, it’s a similarly grim picture for the cutthroat. Its brook-trout-dominated fishery supports “few” cutthroat, and those that remain are “likely the result” of Wyoming Game and Fish Department stocking efforts, Anderson’s report says.

The story is much the same in Jim Creek, the only other Green River tributary in the analysis that still supports cutthroat. Cutthroat in the small stream feeding off of Kendall and Saltlick mountains snowfields have “largely been eliminated” and the brook trout is to blame.

The ongoing shift in fish populations in the Upper Green is testimony to brook trout’s tendency to dominate in the right setting.

“Brook trout mature at an earlier age,” Game and Fish Regional Fisheries Supervisor Hilda Sexauer said. “They grow faster, and they do seem to be able to withstand a little bit more degraded habitat than the Colorado River cutthroat can, but I don’t have any scientific data to back that up.

“They are prolific,” she said, “and when the conditions are right for them, they will just take off.”

At this stage Game and Fish is considering shocking and killing brook trout in portions of the Upper Green watershed, but no chemical removal projects are on the table, Sexauer said.

In small headwater streams, brook trout invasions are enabled by barely noticeable changes in the landscape and then tend to slowly progress.

“All it takes is a boulder to shift or a tree to fall or a really high flow event,” Anderson said. “Brook trout will initially move into a reach where cutthroat have been existing and they’ll coexist for a while. As time goes, they’ll take over.”

The only remaining uninvaded Green River headwaters cutthroat stronghold, Klondike Creek, isn’t immune to a brook trout takeover. Large beaver dams and an irrigation diversion have helped keep the non-native trout out so far, but they aren’t thought to provide a barrier, Anderson said.

Throughout their range, Colorado River cutthroat trout are faring poorly. The speckled, red-throated species of trout is estimated to occupy 16 percent of its historic range, according to a 2010 U.S. Forest Service assessment.

Snake cutties holding up

The Snake River fine-spotted subspecies of cutthroat, by contrast, has better withstood the presence of non-native trout. This resilience held true in the portion of the Upper Green project area that crossed over into the Gros Ventre River drainage, and thus the Snake River watershed.

“Maybe there are more behavioral or physiological differences between the subspecies than we’ve been able to figure out from research,” Anderson said.

Another theory, he said, is that the Snake River’s connectivity supports a full array of age classes of cutthroat that so far have been able to overwhelm isolated populations of brook trout.

While cutthroat were still the most numerous species in the South Fork of Fish Creek — the main Snake watershed stream in the assessment — Anderson found some indications brook trout are tightening their grip. Strawberry Creek, one South Fork Fish Creek tributary, was dominated by brook trout.

In another South Fork of Fish Creek tributary the invasion is happening right now. Raspberry Creek had no brook trout in 1999, the report says, but by 2014 they were present at all three monitoring sites.

“That’s an interesting thing for folks to keep an eye on,” Anderson said. “We need to watch those existing brook trout population in the Snake River and make sure that we keep tabs on any signs of expansion.

“That’s going to be really important for the Snake River fishery,” he said.

For a PDF of Anderson’s report see the online version of this article at JHNewsAndGuide.com.

Contact Mike Koshmrl at 732-7067 or [email protected].